Understanding Childhood and Congenital Glaucoma

Childhood glaucomas include primary congenital glaucoma (also called pediatric or infantile glaucoma) and juvenile glaucoma, which doctors may diagnose after age 3 and into early adulthood.

The congenital glaucomas are rare, but potentially blinding eye disorders. Although they occur only in about 1 out of 10,000 infants, their importance is magnified by the young age of the patients. Doctors diagnose approximately 60% of congenital glaucoma before 6 months of age and 80% before age 1.

In congenital glaucoma, an abnormal drain (trabecular meshwork) in the eye raises intraocular pressure. Doctors classify about half of these cases as primary congenital glaucoma. In this instance, the glaucoma occurs without any other abnormalities in the eye or elsewhere in the body. In the other one-half of babies, there are other abnormalities of the eye or in the rest of the body which are present. These may range from mild to severe. Although genetics can cause congenital glaucoma, most cases occur without inheritance. Most babies with congenital glaucoma are born to healthy parents without a history of glaucoma.

Diagnosing Congenital Glaucoma

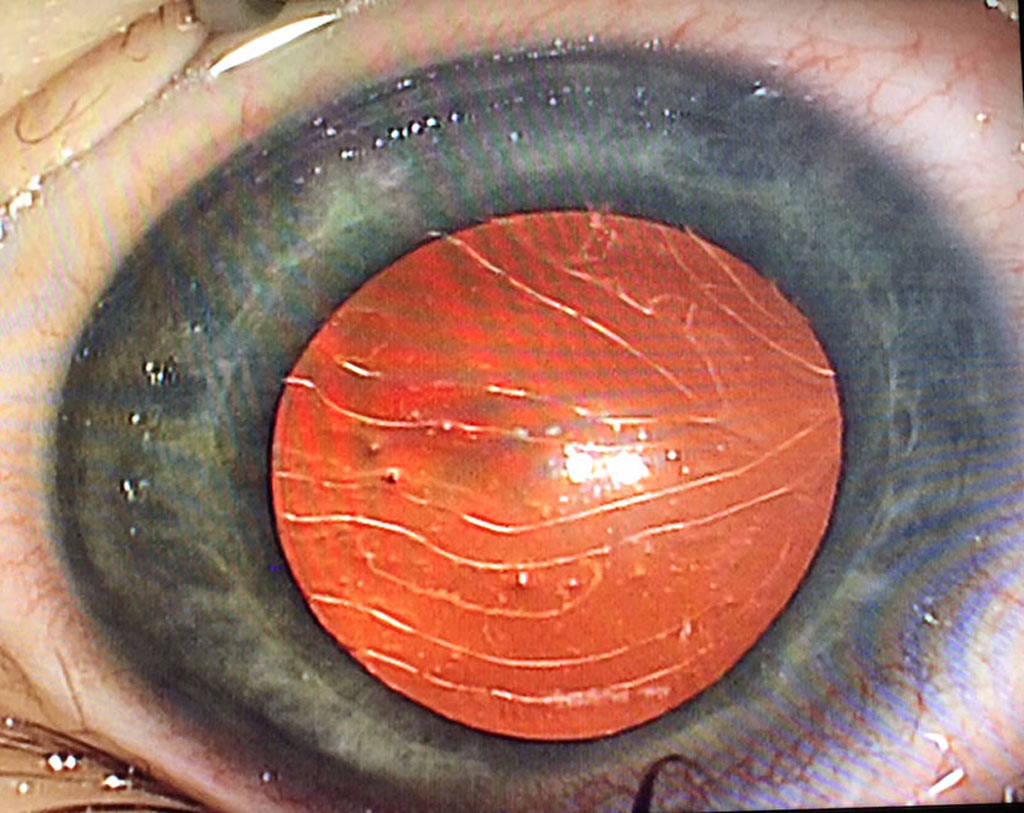

Before the age of three, the wall of the eye is very soft and elastic. Therefore, when the eye pressure rises in congenital glaucoma, the eye enlarges (“buphthalmos”; see Figure 1). Parents or pediatricians often recognize this. After the age of three to four years, the eye is less elastic and does not increase in size when the eye pressure rises.

As the eye enlarges, the inner layer of the cornea, which keeps it transparent, may tear. Haab’s striae are horizontal curvilinear breaks in Descemet’s membrane (one of the inner corneal layers) resulting from acute stretching of the cornea in primary congenital glaucoma (Figure 2). These are in contrast to Descemet’s tears resulting from birth trauma, which are usually vertical or obliquely oriented. As a result, the elevated eye pressure pushes fluid into the cornea, causing it to swell and become hazy (Figure 1).

Parents often notice this as a clouding, whitening, or grayish hue of the cornea. When the condition reaches this stage, the eye may be painful and tearing is present. The baby becomes sensitive to light and attempts to avoid it by covering the eye or burying the head in a blanket. The classic triad of signs/symptoms noted in a patient with primary congenital glaucoma include: epiphora (tearing), photophobia (light sensitivity), and blepharospasm (eyelid twitching).

Uneven Eye Appearance

Although both eyes commonly develop glaucoma, one eye often shows more severe disease than the other. One eye may enlarge more than the other. In some babies, the glaucoma is present only in one eye, particularly when there are other abnormalities. Parents often state that the eye or eyes appear to be becoming more prominent or that one eye is larger than the other.

Several other conditions can mimic congenital glaucoma. The most common of these is tearing due to obstruction of the tear duct, which is outside of the eye. This is not generally a serious condition, and may resolve without treatment. Corneal clouding and eye enlargement indicate a serious condition, so an ophthalmologist should examine the baby as soon as possible.

Treatment for Congenital Glaucoma

Unlike adult glaucoma, which doctors usually treat with eye drops first, doctors often treat childhood glaucoma with surgery. Eye surgery is usually necessary, since treatment with eye drops is only temporarily helpful in many congenital glaucoma. Fortunately, surgical treatment, particularly in glaucoma which develops after the age of six months, is often successful in lowering eye pressure permanently. During the operation, the surgeon opens the poorly functioning drain. This exposes the deepest portions of the drain to the aqueous humor (fluid within the eye).

Doctors have classically treated congenital glaucoma with two operations: goniotomy and trabeculotomy. Surgeons may need to perform them more than once to reduce eye pressure. More recently, doctors have successfully used the GATT procedure for some forms of childhood glaucoma. If these procedures fail, surgeons may recommend other types of surgery.

Most babies with congenital glaucoma maintain some degree of vision, and some may even have excellent vision. With expanding knowledge, the next decade may lead to the discovery of the basic causes of congenital glaucoma and a new form of treatment.

DONATE NOW

DONATE NOW