Types of Glaucoma

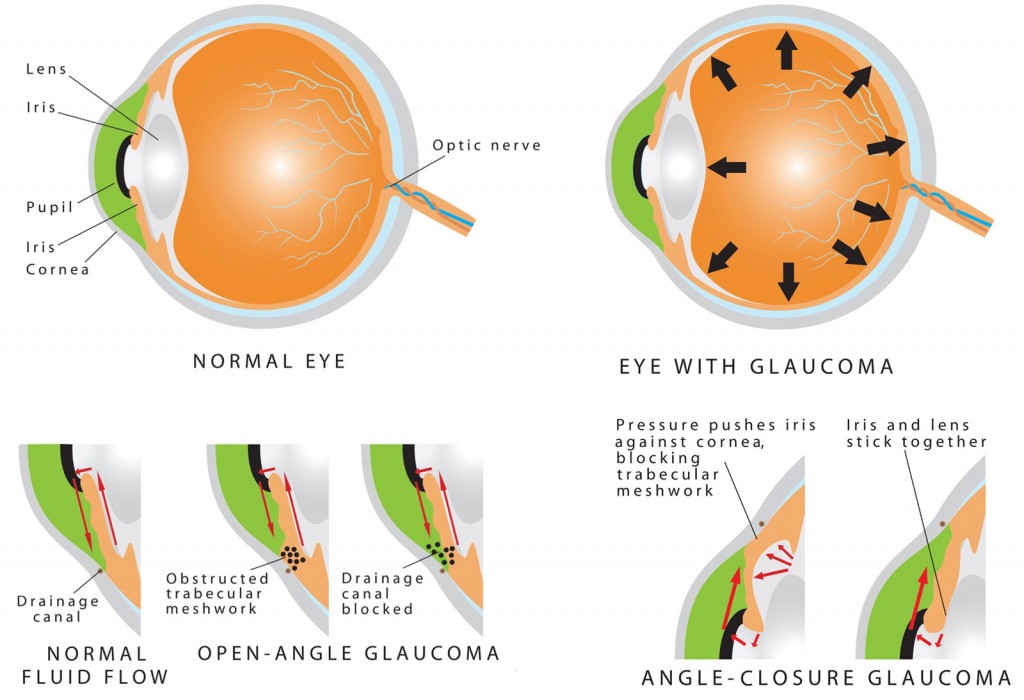

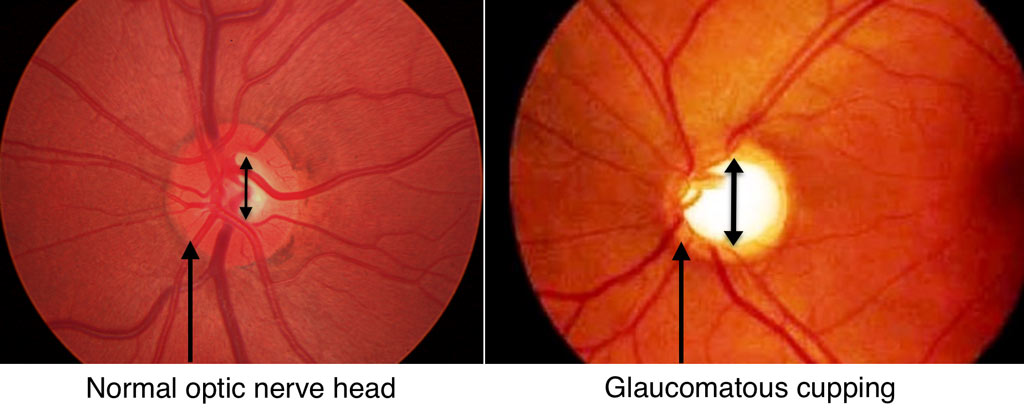

Glaucoma is defined as a group of diseases that cause a characteristic change in the optic nerve with associated loss of visual field/function. More than fifty different causes of glaucoma have been described. Traditionally, glaucomas are classified based on the appearance of the drainage system within the eye, also known as the anterior chamber “angle”. Below, some of the more common types of glaucoma are discussed.

Types of Glaucoma

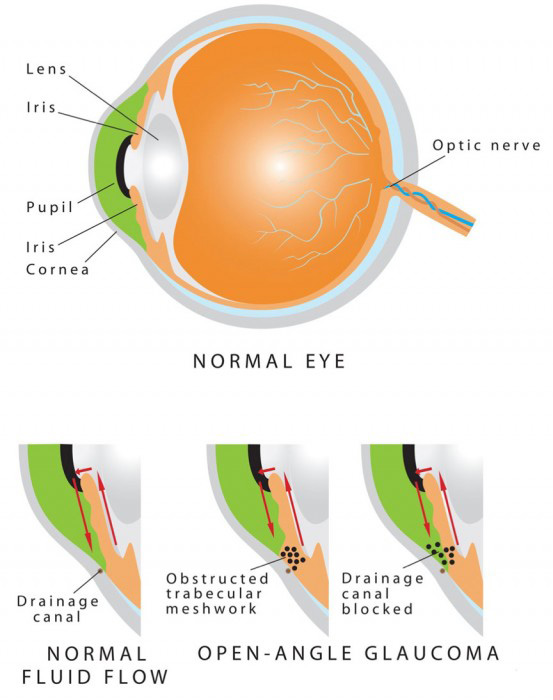

Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma

Primary Open Angle Glaucoma (POAG), also known as chronic open angle glaucoma, is the most frequent type of human glaucoma. It is characterized by elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), cupping and atrophy of the optic nerve head, and typical visual field defects. By definition, in “primary” glaucomas there are no specific ocular abnormalities or systemic diseases causing the glaucoma. Furthermore, gonioscopy of eyes with POAG reveals a normal appearing anterior chamber angle without any obvious abnormalities.

Both eyes tend to be involved at the same time and to a similar degree. The prevalence of POAG in the United States is estimated to be between 1.5% – 2%, with most cases detected after age 40.

Although the cause of POAG is unknown, there are a number of known risk factors including: increased intraocular pressure, advanced age, racial background (African and Hispanic ancestry), decreased corneal thickness, and a positive family history. Evidence also suggests that diabetes and myopia (near sightedness) are also risk factors but to a lesser degree. There is no gender predilection for glaucoma.

Normal Tension Glaucoma (Low Tension Glaucoma)

Normal tension glaucoma (NTG), sometimes referred to as low tension glaucoma (LTG), is often considered to be on a continuum with POAG, with very similar characteristics. While there are a number of subtle differences between POAG and NTG, there is one key difference compared with POAG: eyes with NTG do not have an elevated intraocular pressure as classically defined (usually defined to be greater than 21mmHg).

Treatment for patients with NTG is the same as for all types of glaucoma, namely, lowering the intraocular pressure. Studies have demonstrated that although the eye pressure is not elevated by the normal definition, further lowering of the pressure does decrease the risk of optic nerve damage and visual field loss.

Secondary Open-Angle Glaucoma

Similar to primary open angle glaucoma, patients with secondary open angle glaucoma have an anterior chamber angle which can easily be visualized without obvious obstruction of angle structures. However, in secondary open angle glaucoma, there is an increased resistance to outflow and elevated intraocular pressure associated with an ocular or systemic cause. While the angle can easily be visualized without obstruction, careful gonioscopy often shows subtle changes that your ophthalmologist can detect to give clues as to the cause of the glaucoma.

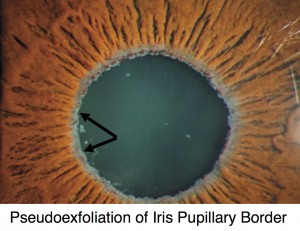

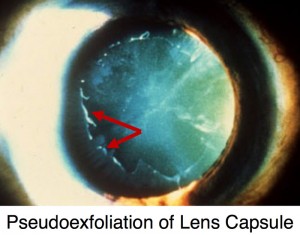

Pseudoexfoliation Syndrome

Pseudoexfoliation Syndrome may lead to a specific type of open angle glaucoma characterized by the deposition of fibrillary material on structures within the anterior chamber, including the iris, lens capsule, zonules, and trabecular meshwork. The disease can be in one or both eyes, and asymmetry of findings is very common. Risk factors for pseudoexfoliation syndrome include age (nearly all patients are older than 50 and most are older than 70), female gender, and Scandinavian descent. Not all patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome develop pseudoexfoliation glaucoma.

Deposition of this material in the trabecular meshwork (part of the anterior chamber angle responsible for drainage), can result in elevated intraocular pressures and subsequent glaucoma. Similar to other types of glaucoma, the treatment for pseudoexfoliation glaucoma is lowering of the intraocular pressure using medicines, lasers, and surgery.

Other findings associated with pseudoexfoliation syndrome include iris atrophy, floppy iris (iridodonesis), poor pupillary dilation, and zonular weakness with lens instability (phacodonesis). Several of these characteristics can make cataract surgery more complex and can be associated with dramatic eye pressure elevations in the immediate post-operative period. The GAT Doctors have tremendous experience with cataract surgery in patients with Pseudoexfoliation Syndrome as well as appropriately caring for patients in the post-operative period.

Pigment Dispersion Syndrome

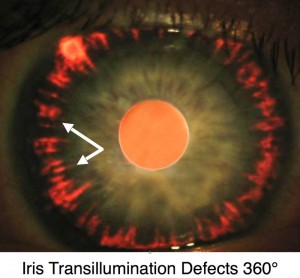

Pigment Dispersion Syndrome is characterized by deposition of pigment on various structures within the eye, including the cornea (Krukenberg spindle), trabecular meshwork, and lens capsule (Zentmayer line). It is further characterized by mid-peripheral iris transillumination defects and is often associated with a posterior bowing of the iris. Risk factors for pigment dispersion syndrome include Caucasian race, male gender, myopia (near-sightedness), and age somewhat younger than most glaucomas, usually between 20 and 50 years. However, not all patients with pigment dispersion syndrome develop pigmentary glaucoma.

Gonioscopy in patients with pigment dispersion syndrome reveals a densely pigmented trabecular meshwork. The syndrome is often characterized by wide fluctuations in intraocular pressure, felt to be a result of increased pigment release into the aqueous humor (fluid within the anterior chamber) with subsequent blocking of the trabecular meshwork.cornea (Krukenberg spindle) Similar to other types of glaucoma, the treatment for pigmentary glaucoma is lowering of the intraocular pressure using medicines, lasers, and surgery. Of note, these patients have been found to respond particularly well to Laser Trabeculoplasty.

Steroid-Induced-Glaucoma

A number of medications, most notably corticosteroids (“steroids”), have been associated with elevation of intraocular pressure. Although topical steroid eye drops and intra/peri-ocular steroids (e.g. intravitreal, intracameral, subtenon, retroseptal) are most likely to cause pressure elevations, any form of steroids including oral, topical creams, nasal sprays, and injections can increase intraocular pressure. While prescription steroid medications are often more potent and more likely culprits, numerous over-the-counter creams and nasal sprays can also cause increased eye pressure.

It is estimated that ~30% of all people have a mild-moderate elevation (up to 11 mmHg rise from baseline) with use of ocular steroids (drops or injectable) and 5% have an elevation of greater than 15 mmHg usually requiring treatment. Among patients with preexisting glaucoma, the likelihood of a pressure elevation rises significantly.isting Glaucoma, The Likelihood Of A Pressure Elevation Rises Significantly.

More recently, it has been observed that patients receiving various multiple non-steroid intravitreal injections (e.g. bevacizumab/Avastin®, ranibizumab/Lucentis®, aflibercept/Eylea®) can also have sustained intraocular pressure rise. These medications are often used for retinal disease including macular degeneration, diabetes, and macular edema (swelling).

Treatment for steroid (medication) induced glaucoma is similar to other secondary open-angle glaucomas and medications are usually successful. Cases requiring surgical intervention also have a high degree of success.

Other examples of secondary open-angle glaucoma include:

- Inflammatory Glaucoma

- Intraocular Tumor-Induced Glaucoma

- Lens Induced Glaucoma (E.G. Phacolytic, Lens Particle, Phacoantigenic)

- Traumatic Glaucoma (E.G. Accidental, Surgical)

- Elevated Episcleral Venous Pressure (E.G. Sturge-Weber Syndrome, Arteriovenous Fistula, Thyroid-Associated Orbitopathy)

Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma

Acute angle-closure glaucoma is a dramatic disorder of sudden onset and represents a true ophthalmic emergency. If not properly diagnosed and treated, progressive and permanent ocular damage occurs in a matter of hours to days. The history is characterized by the sudden onset of pain, redness of the eye, and blurred vision. The pain is usually severe and generally centered over the brow. Nausea, vomiting, and profuse sweating are commonly associated symptoms which may lead to improper diagnosis and treatment in an emergency room setting.

Ocular examination shows a very shallow anterior chamber, corneal edema, and a mid-dilated pupil. Gonioscopy reveals a closed angle without any visible angle structures.

Treatment of an acute angle closure attack is aimed at breaking the attack and lowering the intraocular pressure. Initially, a combination of eye drops and oral medications are used to lower the pressure; miotics (e.g. Pilocarpine) have the additional potential benefit of breaking the attack. A laser iridotomy is usually necessary to break the attack and prevent a repeat attack; the non-affected eye typically requires a laser iridotomy as well to prevent a similar angle closure attack.

There are numerous sequellae of an acute angle-closure attack. Vision is often affected and visual recovery is variable. Following an attack the cornea frequently develops folds in Descemet’s membrane; recovery is usually complete, although some degree of endothelial cell loss may occur. Occasionally, chronic corneal edema develops despite normalized intraocular pressure. This most often occurs in patients with pre-existing Fuch’s dystrophy, or long-standing angle-closure prior to treatment.

During the acute attack, sector ischemia of the iris may occur due to closure of its stromal vessels, and if marked, causes an aseptic anterior uveitis. Ischemic necrosis of the iris causes sectoral atrophy, usually in the horizontal meridian. The pupil may remain permanently dilated and unresponsive to miotics or mydriatics because of iris sphincter damage. In many cases there may also be characteristic “spiraling” of the superficial iris stroma. In such instances, the iris fibers appear to originate at a point near the pupil margin and fan out, in an oblique fashion. Due to the sudden sustained rise in intraocular pressure, lens opacities called glaukomflecken may appear. These opacities represent areas of lens epithelium necrosis. Clinically, they initially appear as small whitish cloudy areas beneath the anterior capsule in the pupillary zone.

Chronic Angle-Closure Glaucoma

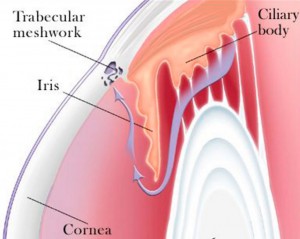

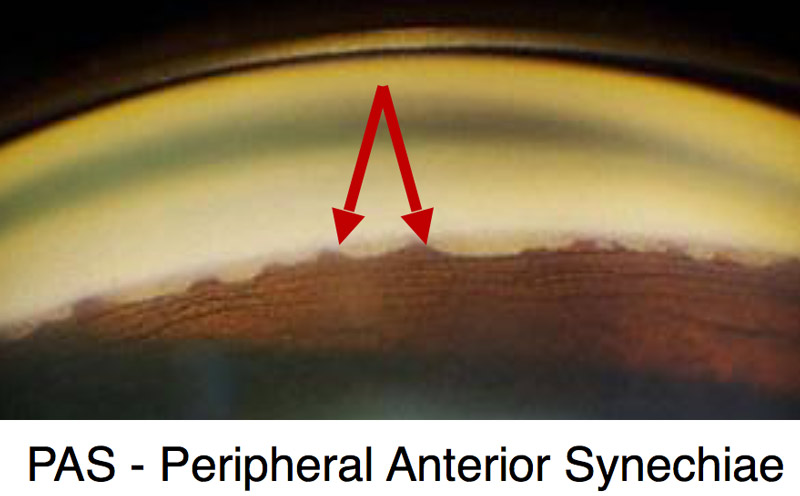

The primary angle-closure glaucomas are conditions which by definition result from obstruction of the anterior chamber angle by iris tissue, without an obvious underlying ocular or systemic cause. In chronic angle-closure glaucoma (CACG), peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS; scar tissue extending between the iris and the trabecular meshwork) close off the anterior chamber angle. This blocking of the trabecular meshwork ultimately causes elevation of the intraocular pressure. Angle-closure glaucoma caused by a pupillary block mechanism can be divided into either acute (discussed above) or chronic angle-closure. The initiating event is a functional block between the anterior lens surface and the posterior pupillary portion of the iris. This results in trapping of aqueous in the posterior chamber thus pushing the peripheral iris forward and closing of the angle; outflow resistance increases, intraocular pressure rises, and with time permanent synechial closure ensues.

Chronic angle-closure glaucoma is often overlooked as a diagnosis and may be mis-treated as primary open-angle glaucoma. Gonioscopy is the key to their recognition and classification. A thorough knowledge of the normal angle is imperative before the subtle changes of PAS formation can be discovered and quantitated. Such knowledge is dependent on the ability to visualize all aspects of the angle, a skill all GAT Doctors have as a result of their fellowship training in glaucoma.

Similar to other forms of glaucoma, the primary treatment for CACG is lowering of the intraocular pressure. However, treatment of the pupillary block component of the disease with a laser iridotomy is important. The goal of a laser iridotomy is to slow or stop progressive PAS formation and angle dysfunction. Even with a patent iridotomy, progressive angle closure may occur and therefore serial gonioscopy is imperative. Most patients are adequately treated with medical therapy, though glaucoma surgery may be necessary.

Secondary Angle-Closure Glaucoma

Similar to primary angle-closure glaucoma, patients with secondary open angle glaucoma have an anterior chamber angle which at least partly occluded, often permanently by peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS; scar tissue extending between the iris and the trabecular meshwork). However, in secondary angle-closure glaucoma, the occlusion of the angle is associated with an ocular or systemic cause. Careful gonioscopy often shows subtle changes that your ophthalmologist can detect to give clues as to the cause of the angle closure, a skill all GAT Doctors have as a result of their fellowship training in glaucoma.

Neovascular Glaucoma

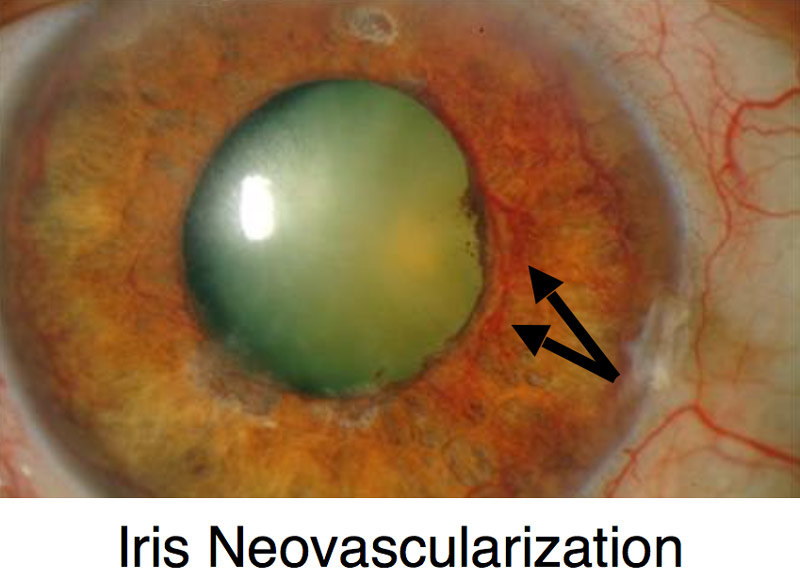

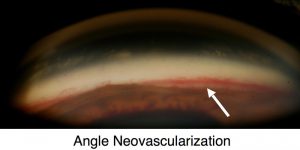

Neovascular glaucoma, a severe type of secondary angle-closure glaucoma, results from the formation of abnormal blood vessel growth in the iris and trabecular meshwork. This abnormal neovascularization (new blood vessel growth) is associated with bleeding and scarring within the eye, as well as PAS formation in the angle leading to secondary angle-closure glaucoma.

Like all forms of secondary glaucoma, neovascular glaucoma is the result of other ocular and/or systemic disease. The most common causes of neovascular glaucoma include diabetes mellitus, central retinal vein occlusions, and ocular ischemic syndrome. Other causes included chronic inflammation, trauma, tumors, radiation, and other diseases affecting blood vessels (both in the eye and systemically).

Patients with neovascular glaucoma often present with acute (sudden) vision changes, pain, eye redness, and high intraocular pressure. Treatment is two-fold: controlling the intraocular pressure and treating the underlying disease. Controlling the intraocular pressure can be difficult with medications alone and surgical intervention is often necessary, usually with a glaucoma drainage implant.

Of note, blood vessels are present in the normal angle and can often be seen upon routine gonioscopy. To a marked extent, their visibility depends upon the color of the iris, and to a lesser extent, upon the width of the angle. Gonioscopically visible blood vessels can be seen in more that 50% of blue-eyed individuals, but less than 10% of brown-eyed humans. They are more commonly noted in wide than narrow angles. The GAT Doctors perform gonioscopy on all patients and are experts at distinguishing normal versus abnormal angle blood vessels.

Inflammatory Glaucoma

Ocular inflammation can lead to a variety of problems, including elevated intraocular pressure, glaucoma, corneal disease, cataracts, and retinal disease, as well as scarring in the conjunctiva, cornea, iris, anterior chamber angle, and retina.

Inflammatory glaucoma results from a variety of mechanisms, with formation of PAS and posterior synechiae (scar tissue between the iris and the lens) ultimately leading to elevated intraocular pressure. Similar to other forms of secondary glaucoma, the most important treatment aims at the underlying cause, often with topical and/or oral steroids and other anti-inflammatory medications. Treatment of elevated intraocular pressure is initially done with glaucoma medications, though surgical treatment is often necessary due to the aggressive nature of inflammatory glaucoma.

Glaucoma Suspect (Borderline Glaucoma)

Patients who are deemed to be a glaucoma suspect (borderline glaucoma) may show some signs of glaucoma without definitive disease, or may carry risk factors for developing glaucoma. Often, patients are classified as “low risk” or “high risk” glaucoma suspects based on the number of findings or risk factors. Classically, patients described as a glaucoma suspect had one of the following:

- Optic nerve or nerve fiber layer suspicious of glaucoma

- Intraocular pressure of greater than 21 mmHg

- Visual field changes consistent with glaucoma

Several criteria have been associated with an increased risk of glaucoma. Patients may also be considered if they have some of the following:

- Level of Intraocular Pressure Rise

- Cup-to-disc Ratio (optic Nerve Appearance)

- Family History of Glaucoma

- Age

- Race

- Central Corneal Thickness

- Associated Diseases (e.g. Diabetes, Myopia)

Although there is no way to know which glaucoma suspects will ultimately develop glaucoma, your ophthalmologist will discuss your risk factors with you and follow your at regular intervals.

Narrow Angle and Plateau Iris Syndrome

Plateau Iris SyndromeWhile both a narrow angle and plateau iris can be associated with development of angle closure glaucoma, they are not synonymous with glaucoma. Rather, both a narrow angle and plateau iris are anatomic descriptions of the anterior chamber angle between the cornea and iris.

Narrow Angle

Patients with a narrow anterior chamber angle are at risk for developing both acute and chronic angle-closure glaucoma. Numerous studies have attempted to predict which patients will go on to develop glaucoma, but none have been consistently validated. Not all patients with narrow angles necessarily need treatment. However, those with intraocular pressure elevation, peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS), appositional angles, history of previous angle closure, positive family history, and/or symptoms of intermittent angle closure should be treated with a laser iridotomy. Regardless of a whether a patient is treated or not, all those with a narrow angle should be warned of the signs/symptoms of an angle closure attack or intermittent angle closure, including: eye pain, eye redness, blurry vision, multi-colored halos, headache, nausea, and vomiting.

Several systemic medications including cold and allergy medications, urological medications, and anti-depressants are associated with an increased risk of an acute angle-closure attack. Please let your ophthalmologist know if you take any of these types of medications with any regularity, as their use may influence your doctor’s decision to treat you.

Plateau Iris Syndrome

The plateau iris configuration refers to an anterior chamber of normal depth centrally with a flat iris plane, but a narrow angle on gonioscopic examination. Often confused with a narrow angle secondary to papillary block (described above), one should be suspicious of a plateau iris in younger patients with myopia in the setting of an acute angle closure attack. Although the mechanism of plateau iris is different than that of a narrow angle with pupillary block, the initial treatment with a laser iridotomy is the same; some anterior chamber angle widening may be noted, but patients with a plateau iris will have a persistent narrow angle despite patent iridotomy (hole in the iris). These patients are often discovered when an angle-closure attack occurs in the presence of a patent iridotomy. The mechanism appears to be an abnormality of the peripheral iris and anterior rotation of ciliary processes which allows occlusion of the trabecular meshwork on dilation of the pupil. Additional treatment for patients with plateau iris may include close observation, miotic medications, laser iridoplasty, or lens/cataract extraction.

Childhood Glaucoma (Congenital Glaucoma)

Childhood glaucomas encompass both primary congenital glaucoma (also called pediatric or infantile glaucoma) as well as juvenile glaucoma which may be diagnosed after age 3 and into early adulthood. Please refer to Childhood (Congenital) Glaucoma page for more information.

DONATE NOW

DONATE NOW